On the south-eastern shores of Britain is a town of rescuers, tooth-white cliffs hanging over the sea and an unscalable fortress. This is Dover, a town I tried to visit twice and did not succeed. The first time I was on a budget, the second time I did not have enough time. This time it was both: I am on a budget AND I did not have much time, but I still managed. And, oh boy, am I lucky and happy and dying to share my day with you.

Once in Dover, I grabbed a wake-up coffee, admired the mighty castle on the hill, and headed straight toward the White Cliffs hike. I didn’t budget for the castle this time (the entrance is €25), but it does look majestic from the outside. Beneath it lie tunnels that played a crucial role in the Dunkirk evacuation.

The castle itself sprawls across a green hill, its dark stone towers and walls forming the largest castle in England. Because of its strategic position overlooking the narrowest point between England and continental Europe, it was known as the “Key to England.” The idea was simple: conquer Dover, and England would be on its knees. Yet nobody ever managed to take these walls—not by direct military assault, at least. Siege after siege, the towers stood unshaken.

And they still stand today, tall and unmissable, watching over Britain from above. They almost give the impression of silently judging everything beneath them. Reminds me of cats. Anyway, where was I? Oh yes, The White Cliffs of Dover.

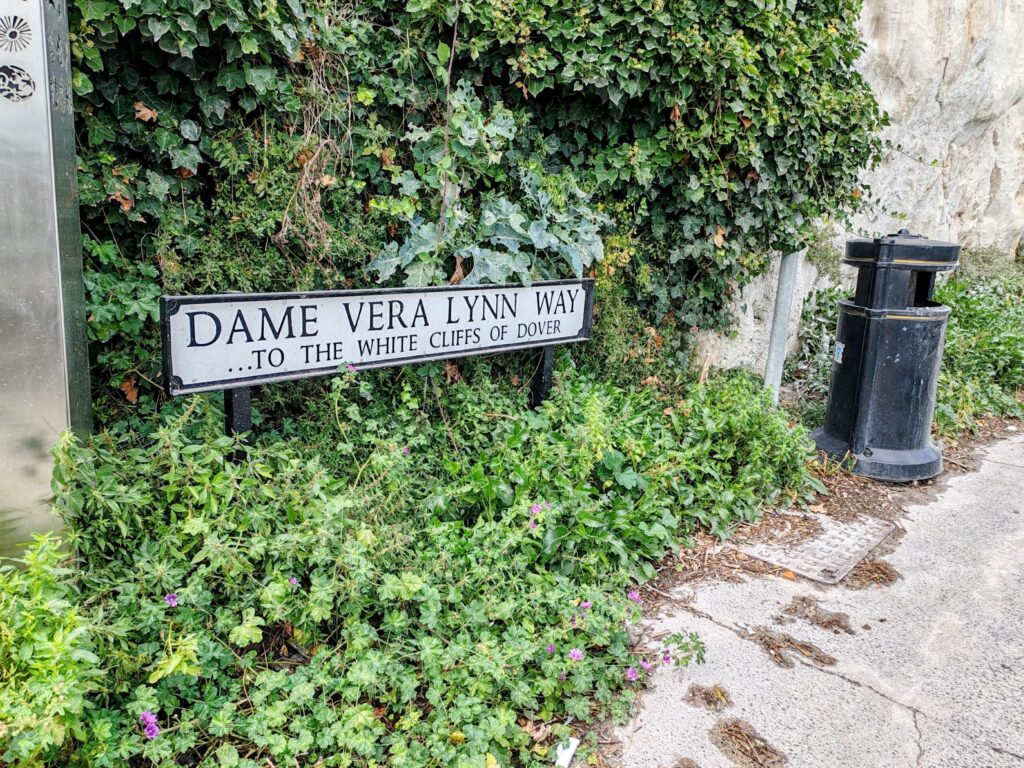

It took me about 30 minutes to walk from the town center to the start of the trail. At first, the asphalt road leads the way, but soon it becomes Dame Vera Lynn Way, guiding you under one of the white cliffs and then up to the top of another. As the path rises, the sea suddenly opens before you, ships gliding across the Channel. Behind you, the castle lingers, half-hidden by the bushes on the hillside.

Soon, I reached a parking lot—and just beyond it, the nature trail begins. The first sign points toward the lighthouse and “beautiful views,” and that’s when you know: this is the way to go.

There’s a small nature center here where you can buy snacks, drinks, and postcards painted by a local artist. Looking at them, you can tell she knows these hills by heart—capturing the trails as they once were, the stones under the cliffs washed by waves, every detail of this familiar landscape brought to life.

From here, the trail leads you down and then up again, with unmissable views along the way. On the safety fence, keeping you from falling into the sea (which must be epic, but let’s skip that), you’ll find small boards sharing curious facts about the area: the age of the chalk cliffs, or the story of the first person to cross the Channel back in 1875.

And then, of course, there’s the view—the brilliant white cliff, the waves crashing against the shore beneath, the trail itself stretching ahead. From this point, you can see almost the entire route, with small figures scattered along the path that carve pale lines through the green land. Even the wild, merciless winds add a touch of suitable drama to the scene.

Following the winding path that mirrors the edges of the cliffs, I passed cows grazing calmly, butterflies resting on rare flowers, and trees dressed in red berries. At last, the trail curves to the left and ends at the base of a Victorian-era lighthouse, shining white against the sky.

Here you’ll find picnic tables, toilets, and—if you arrive before five o’clock—an atmospheric tea room. Sitting under the historic roof of the South Foreland Lighthouse, sipping hot tea and watching a school group through lace curtains, I took a pause. A pause from the rush, from busy days, from a summer packed with work and studies. Suddenly it all felt so distant and i was left with just NOW.

Now was the warmth of the tea, the sweetness of a scone with cream and jam, the wind howling outside and bending the plants, the old walls holding centuries of stories. What curious stories might have unfolded inside these walls all the way since 1843? Well, we can only wonder. What we do know is that this lighthouse is as important as anything in Dover—after all, it was the first in the world to shine with electric light.

The school group started to move away and, after some time, I followed. I pulled my collar up, my scarf on top, and back into the raging wind. This is a circular trail and the path runs back just behind the lighthouse. The path back is a bit more high, overlooking the sea from one side and greeny fields from the other. The whole circular trail is about 6km long. As I made my way back along the cliffs, I gazed out over the Channel, thinking of all the armies that once tried to cross it—dreaming of tasting local scones and wandering these green hills for themselves. Yet so many of them were turned away before ever setting foot here, driven back by storms and relentless winds.

There is something special about the wind on these cliffs—it rages, but it feels warm; it howls, yet somehow it cares. Perhaps it has always been like this for those who walk on this side.

I was reminded of Cate Blanchett’s Queen Elizabeth in Kapur’s film, when she cries: “I too can command the wind, sir! I have a hurricane in me that will strip Spain bare if you dare to try me!”

And you know what? Walking these trails beneath the warm but untamed wind, I can’t help but wonder—maybe they really DO command the wind here. Maybe that’s just what the wind does on the land of England—help the locals, but send strangers back across the sea, just like the tide always returns what doesn’t belong.

I wandered back to the nature center, picked up a craft beer from the Kent region (anyone surprised?), and followed the now-familiar path toward town. Half an hour walking here, half an hour walking there—hiking these lands feels like something you never want to end, so why not keep going, I thought.

I added a few extra kilometers trying to find Shakespeare Beach (lovely name, isn’t it?). At some point, I realized I could wander forever—or at least until my train left—but without a car, the place was out of reach. So I turned back. More steps in Dover.

By then the town was slipping into sleep: streets were empty, only a few pubs still buzzing with voices. I found the train station, and though I still had time to spare, I stayed outside. Something in me wanted to keep walking endlessly.

I put on Bridge City Sinners in my headphones. They somehow sound joyful and desperate at the same time, and it fit perfectly. I strolled through quiet streets lined with houses that looked both dark and colorful—a strange mix, but exactly right with this music. After three songs, I turned back, now facing the mighty castle looming over the town.

Everything around me felt steeped in history yet shaded in somber colors. Even the sunset was subtle and pale, carrying its own quiet drama. I caught myself thinking that these streets should be walked by punks, goths, or people in Victorian suits—anything else feels not quite enough.

Half an hour later I caught my train, and when I finally reached the hostel I only managed two hours of sleep. But even during those hours I was still walking the same Dover streets, looking up at the timeless castle. Only now the streets never ended, and the people around me wore Victorian dresses, gothic fashion, and eccentric punk outfits—as if the town itself had decided to dress the way that fits my perception.